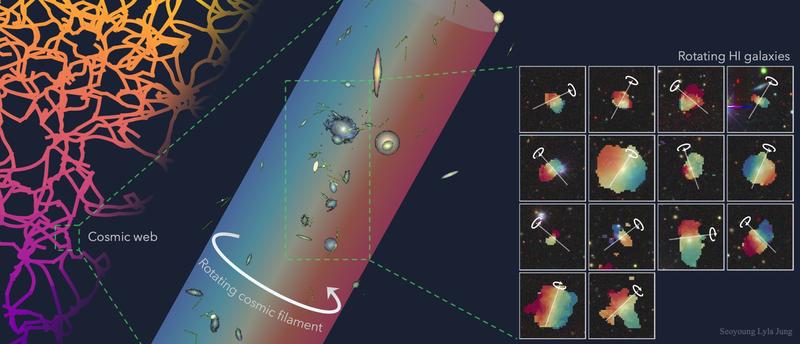

A figure illustrating the rotation of neutral hydrogen (right) in galaxies residing in an extended filament (middle), where the galaxies exhibit a coherent bulk rotational motion tracing the large-scale cosmic web (left). Credit: Lyla Jung

A deep-space survey led by St Cross Fellow Professor Matt Jarvis has enabled the discovery of one of the largest rotating structures ever detected: a remarkably thin string of galaxies embedded within a giant, spinning cosmic filament around 140 million light-years away.

Cosmic filaments are vast, thread-like structures that form part of the Universe’s underlying framework. They guide the flow of gas and matter into galaxies, influencing how galaxies grow and how they acquire their spin. Discoveries of filaments that rotate, and contain many galaxies spinning in the same direction, are extremely rare. They therefore offer valuable clues about the early stages of galaxy formation.

The newly identified filament appears young and relatively undisturbed. It contains at least 14 hydrogen-rich galaxies arranged in an exceptionally thin line more than five million light-years long, all sitting within a much larger structure containing over 280 galaxies. Many of these galaxies rotate in the same direction as the filament itself, a pattern that challenges existing models of how cosmic rotation develops.

This discovery was made using MIGHTEE (MeerKAT International GHz Tiered Extragalactic Exploration), a deep-sky radio survey led by Professor Jarvis and carried out with South Africa’s powerful MeerKAT radio telescope. By combining these observations with optical data from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, the team were able to map both the alignment of galaxy spins and the rotation of the filament.

Professor Jarvis said:

This really demonstrates the power of combining data from different observatories to obtain greater insights into how large structures and galaxies form in the Universe. Such studies can only be achieved by large groups with diverse skillsets, and in this case, it was really made possible by winning an ERC Advanced Grant/UKRI Frontiers Research Grant, which funded the co-lead authors.

Because hydrogen gas is the most abundant element in the Universe and is the fundamental building block of all the galaxies we can see, it acts as a sensitive tracer of how material flows along the filament. This helps researchers build a clearer picture of how galaxies gather fuel, form stars, and develop their characteristic rotation over cosmic time.

The finding also matters for future cosmology missions, such as ESA’s Euclid mission and the forthcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory, where understanding how galaxies align within large structures is crucial for interpreting observations of dark matter and the expanding Universe.

The study involved collaborators from the University of Cambridge, the University of the Western Cape, Rhodes University, the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory, the University of Hertfordshire, the University of Bristol, the University of Edinburgh, and the University of Cape Town.

The research paper, ‘A 15 Mpc rotating galaxy filament at redshift z = 0.032’, is published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.